Download the Essay (PDF) 4.1 MB

By Frances Contreras

Introduction

Much of the diversification in American society and the higher education system is due in part to the increasing Latinx population.[1] Between 1995–96 and 2015–16, the representation of Latinx students among all undergraduate students nearly doubled from 10.3 percent to 19.8 percent (Espinosa et al. 2019). This trend is predicted to continue, with Latinx students seeing the largest growth among all public high school graduates by 2025. Additionally, the college enrollment rate of recent Latinx high school graduates is predicted to inch up slightly higher than that of White students—70.6 percent and 70.5 percent, respectively (Espinosa et al. 2019). With the current and projected increase of Latinx student enrollment in higher education, institutions with the Hispanic-serving designation will also continue to rise.

As institutions that serve undergraduate student bodies of 25 percent or more Latinx students, Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs) are a relatively recent phenomenon in the history of higher education (Laden 2002; Contreras et al. 2008).[2] The number of HSIs around the country has grown substantially in the past two decades, driven by states with a sizable and rapidly increasing Latinx population. As a result, HSIs represent a significant opportunity to increase Latinx college access and completion rates (Contreras and Contreras 2015; Hurtado, González, and Calderón Galdeano 2015).

California is unique among states with high Latinx populations in that every public education system in the state is now an HSI system—an enrollment sea change that has taken place over the past 20 years.

And while two-thirds of all Latinx students enrolled in postsecondary education attend an HSI, there is an emerging body of literature in higher education that questions the degree to which Latinx students are served as opposed to simply enrolled (Hurtado, González, and Calderón Galdeano 2015; Malcom, Bensimon, and Davila 2010; Garcia 2016; Garcia and Taylor 2017). There is even a proposed framework for “servingness” at HSIs that unpacks select institutional markers and practices of responding to the needs of Latinx students (Garcia, Núñez, and Sansone 2019).

California is unique among states with high Latinx populations in that every public education system in the state is now an HSI system—an enrollment sea change that has taken place over the past 20 years (Contreras 2018). More specifically:

- Latinx students represent 55 percent of the K–12 population in California.

- Among community colleges in California, 103 out of 114 are HSIs (Excelencia in Education 2019b; California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office 2019).

- Twenty-one out of 23 California State Universities (CSUs) are HSIs (Excelencia in Education 2019b).

- Six out of nine (undergraduate degree-granting) University of California system (UCs) institutions are HSIs, with two additional UC campuses as emerging HSIs (Contreras 2018).

In fact, California is home to a third of the country’s HSIs (approximately 170) (Excelencia in Education 2019b), and the state is home to 48 “emerging HSIs”—colleges and universities with at least 15 to 24 percent of their undergraduate student body composed of Latinx students (Excelencia in Education 2019a). Beyond California, HSI growth extends beyond the five southwestern states where these institutions have been historically dominant—today HSIs are located in 25 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico (Excelencia in Education 2019b).

Systemic and Institutional Challenges to Becoming “Latinx Responsive”

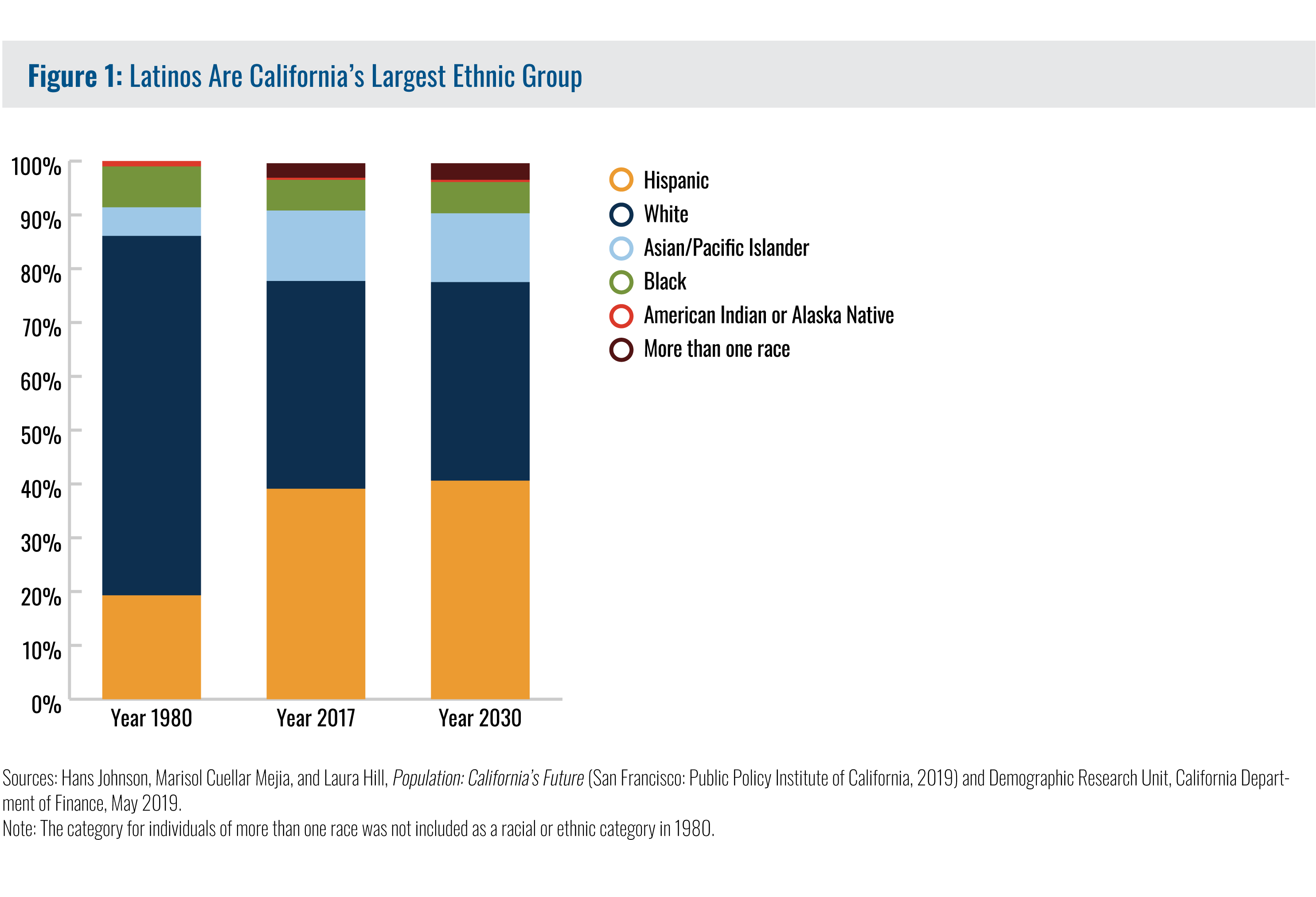

According to recent population projections, Latinx individuals will represent one-quarter of the U.S. population in 2045. California is an important bellwether state for the rest of the nation given the demographic shifts and increases that are occurring among the Latinx population (Figure 1). As a result, California serves as an example for the array of approaches and educational policies to address the needs of Latinx college goers, including approaches across the P–20 education continuum—addressing academic supports, preparation in the K–12 sector, and Latinx students’ desire to stay connected to family and their support networks (Contreras 2011; Gándara and Contreras 2009).

Given the sizable presence of HSIs in California and growth elsewhere, institutions need to transform their infrastructures to better serve Latinx students—to examine their approaches to responding to the needs of a diverse, largely bilingual and bicultural population. Such approaches require faculty and staff, and especially institutional leaders, to review and enact culturally relevant practices that prioritize a student-centered approach in all aspects of the institution. Culturally relevant pedagogy and practice enables students to experience academic success while developing cultural awareness and maintaining their own culture (Ladson-Billings 1995). Moreover, becoming “Latinx responsive” entails a greater understanding of the inequities that exists throughout the P–20 education continuum and the supports needed to mitigate the uneven resources and investments made in Latinx students.

Given the sizable presence of HSIs in California and growth elsewhere, institutions need to transform their infrastructures to better serve Latinx students—to examine their approaches to responding to the needs of a diverse, largely bilingual and bicultural population. Such approaches require faculty and staff, and especially institutional leaders, to review and enact culturally relevant practices that prioritize a student-centered approach in all aspects of the institution. Culturally relevant pedagogy and practice enables students to experience academic success while developing cultural awareness and maintaining their own culture (Ladson-Billings 1995). Moreover, becoming “Latinx responsive” entails a greater understanding of the inequities that exists throughout the P–20 education continuum and the supports needed to mitigate the uneven resources and investments made in Latinx students.

Becoming “Latinx responsive” entails a greater understanding of the inequities that exists throughout the P–20 education continuum and the supports needed to mitigate the uneven resources and investments made in Latinx students.

Segregation as a Historical Backdrop to K–12 Inequity

The systemic shortcomings of college preparation in P–12 education for Latinx students can be seen by examining school segregation. California has the highest percentage of Latinx students who attend segregated schools, which are almost always overwhelmingly populated with low-income students (Frankenberg et al. 2019). In fact, over half of Latinx students in California attend an “intensely segregated” non-White school, defined as 90–100 percent non-White students (Frankenberg et al. 2019).

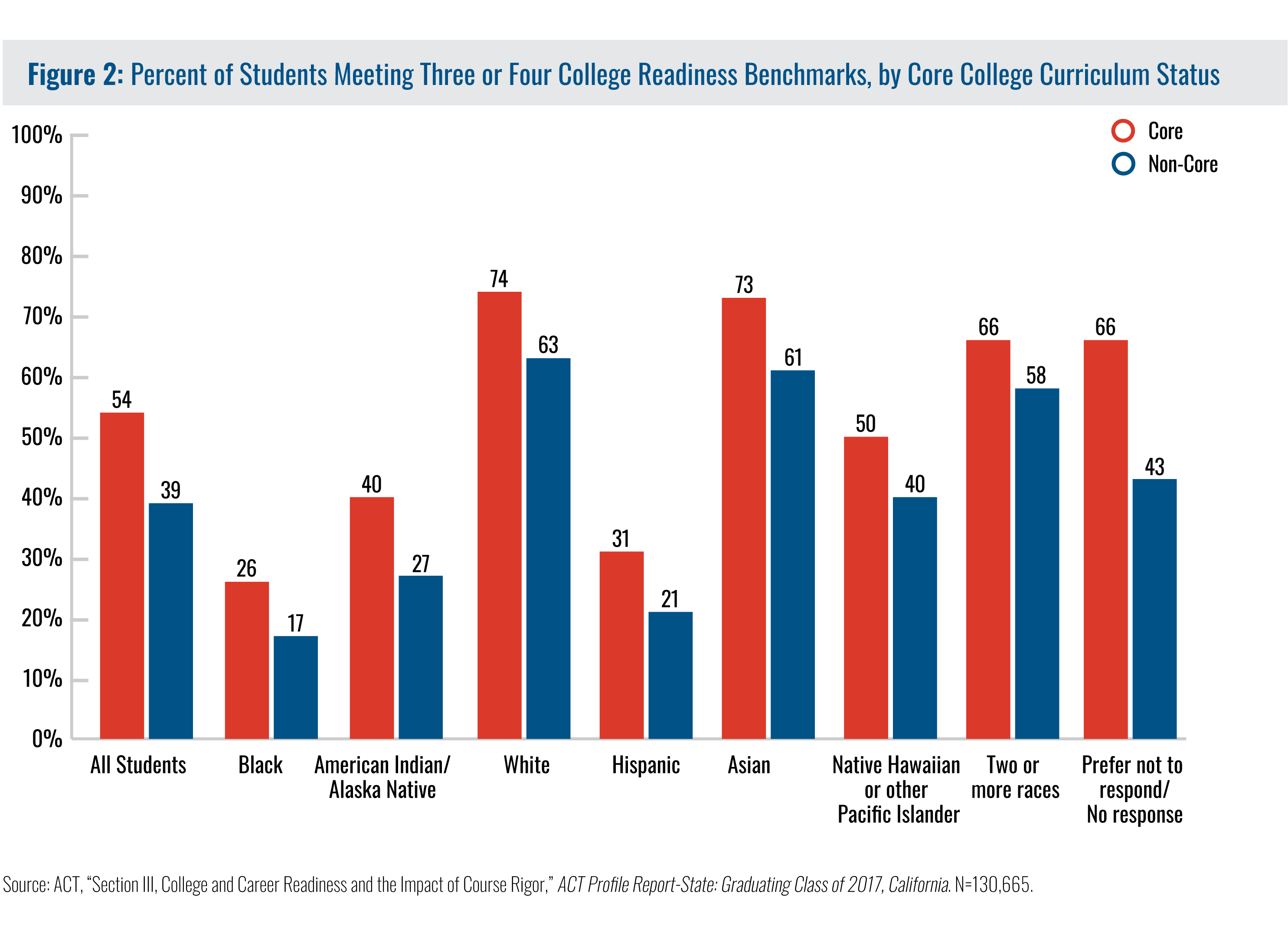

A combination of these and other factors have been found to influence achievement gaps. For example, less experienced teachers are usually distributed to schools with greater proportions of Black and Latinx and low-income students (Wagner 2017). Additionally, these schools often offer fewer upper-level math and science courses and fewer AP and gifted/talented education programs, and overall funding is typically lower, which provides even fewer opportunities for college preparation (Wagner 2017). The systemic shortcomings of these schools can also be seen in the ACT test scores of Latinx students, as a low percentage of Latinx test-takers meet the higher-level college readiness benchmarks (ACT 2017) (see Figure 2).

This lack of college preparation shows up in the community college sector, in particular. Over 75 percent of entering Latinx students need developmental education in math and English, with only 27 percent and 44 percent, respectively, transitioning out of these courses (Mejia, Rodriguez, and Johnson 2016). Moreover, only 30 percent of Latinx students who begin community college in California with aspirations to transfer to a four-year institution actually transfer.

This lack of college preparation shows up in the community college sector, in particular. Over 75 percent of entering Latinx students need developmental education in math and English, with only 27 percent and 44 percent, respectively, transitioning out of these courses (Mejia, Rodriguez, and Johnson 2016). Moreover, only 30 percent of Latinx students who begin community college in California with aspirations to transfer to a four-year institution actually transfer.

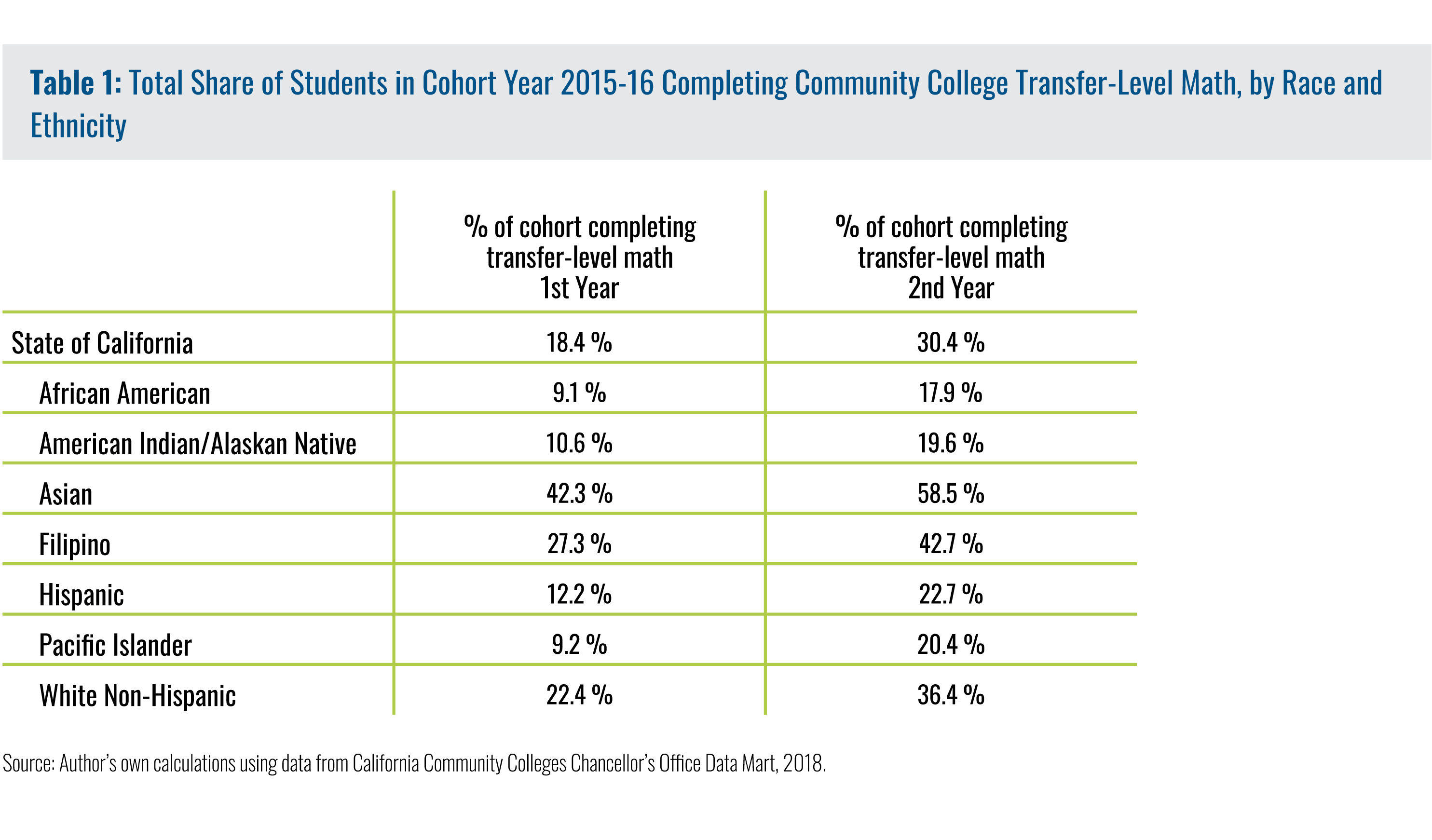

Such low transfer levels are troubling given that 58 percent of Latinx students in California begin their higher education career at a community college. Part of the problem is transfer eligibility. Transfer data from California Community Colleges convey very low percentages of Latinx students meeting this eligibility, partly due to the low rate of completion of transfer-level credits. Data on achievement in transfer-level math, collected by the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office and housed in its Data Mart website, show only 12.2 percent of Latinx students who started college in 2015–16 complete this requirement by their first year, and only 22.1 percent by the second year (see Table 1). One major reason is related to remediation. However, a number of changes are occurring in California through the policy arena, such as the recently adopted Guided Pathways framework, where college-level course taking is accelerated to facilitate higher transfer rates.

These data reinforce the need for colleges and universities, especially community colleges, to consider students’ enrollment patterns and college-going behavior. For example, Latinx community college students in California largely enroll part time, yet student service infrastructures, financial aid, and courses themselves are largely predicated on a full-time model (Contreras and Contreras 2015). This presents a fundamental disconnect with the changing demands of the community college student.

These data reinforce the need for colleges and universities, especially community colleges, to consider students’ enrollment patterns and college-going behavior. For example, Latinx community college students in California largely enroll part time, yet student service infrastructures, financial aid, and courses themselves are largely predicated on a full-time model (Contreras and Contreras 2015). This presents a fundamental disconnect with the changing demands of the community college student.

Becoming “Latinx Conscious and Responsive” in California

Latinx students continue to represent a larger and larger share of California’s undergraduate population, and are the largest pool of applicants to both the CSU and UC systems. For students to reap the full benefits higher education has to offer, institutions must rise to meet students where they are and serve them through to completion. To do so, California’s public higher education system has taken steps toward becoming “Latinx responsive.”

For students to reap the full benefits higher education has to offer, institutions must rise to meet students where they are and serve them through to completion. To do so, California’s public higher education system has taken steps toward becoming “Latinx responsive.”

California Community Colleges

In becoming Latinx responsive, California Community Colleges are engaged in an effort to accelerate developmental education through the Carnegie Math Pathways project, a partnership with WestEd. This effort reduces the number of required developmental courses to one course (either Statway or Quantway), with academic supports. The project has shown promise for community college students in reducing their overall time in a developmental course, as well as degree completion and transfer. A WestEd study compared Pathways students with students in traditional developmental math courses: a higher percentage of both Statway and Quantway students either earned college-level math credit within one year or passed developmental math than students in the traditional math sequence (Ganga and Mazzariello 2018). Moreover, overall efforts to diversify math pathways (in addition to Statway and Quantway) have yielded two, three, and four times the completion rates of traditional pathways, also in less time (Burdman et al. 2018).

California State University System

Similar to the challenges that exist in California’s community college system, the California State University system has great discrepancies across race and ethnicity when it comes to degree completion. For Latinx students, this is a critical shortcoming given that 21 out of 23 CSU campuses are HSIs. An analysis by the Public Policy Institute of California revealed that in 2015, the six-year graduation rate for Latinx and African American students was much lower, when compared with the graduation rate for Asian and White students (Jackson, Jacob, and Cook 2016).

In 2015, the CSU system launched Graduation Initiative 2025 to dramatically increase undergraduate college completion rates for Latinx and other students of color. The initiative has brought greater attention to graduation and completion across the CSU campuses, including a more transparent infrastructure for monitoring degree completion. While the progress reporting does not segment the outcomes by specific racial or ethnic groups, a 2018 progress report published by the system reported that these efforts narrowed the equity gap by 14 percent for underrepresented students of color and by 10 percent for students receiving Pell Grants (CSU 2018). Additionally, nearly all campuses have increased their overall four-year graduation rate (CSU 2019).

University of California System

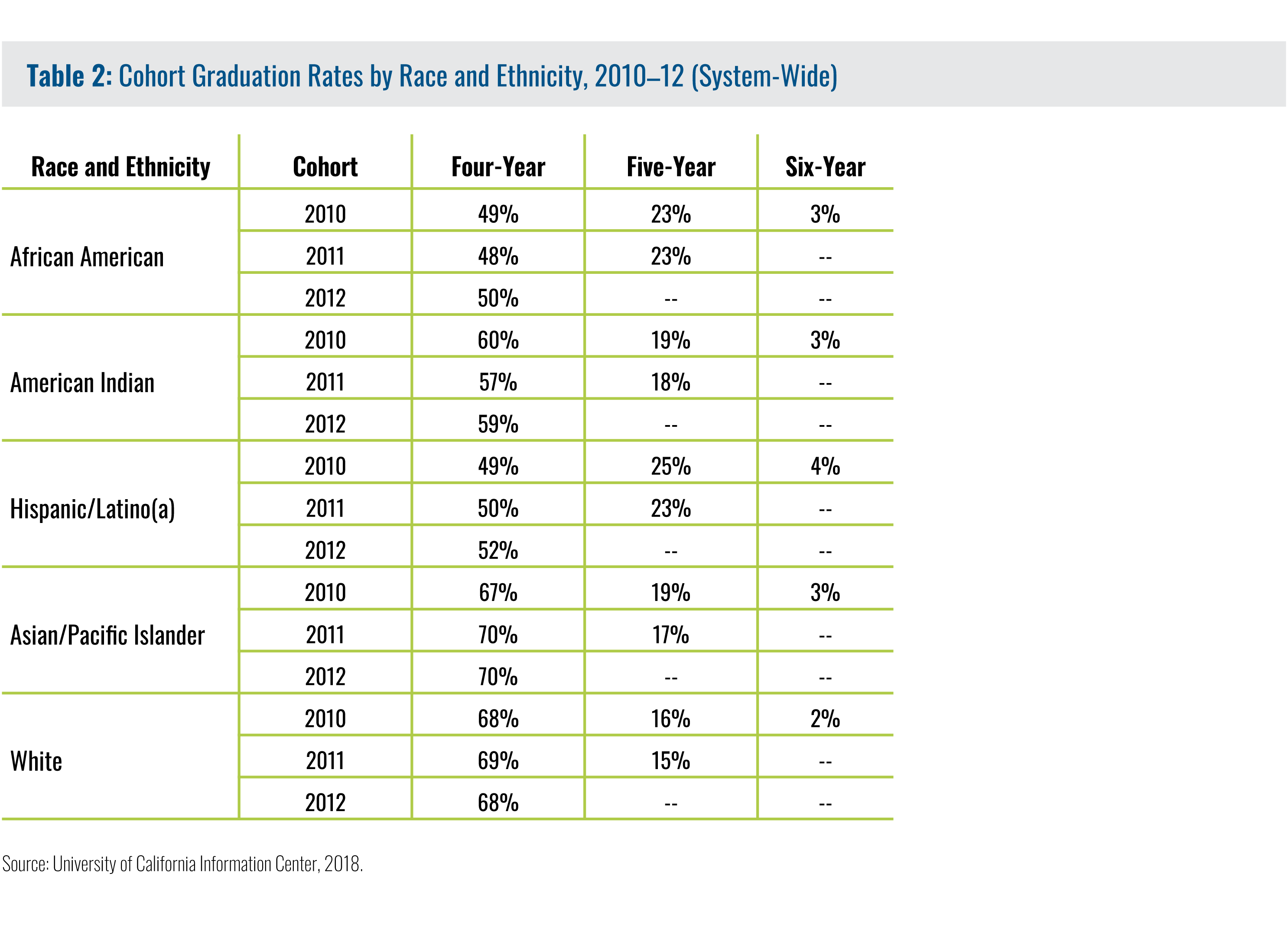

The six-year graduation rates for Latinx students across the University of California system is well above the national average, at 84 percent. This rate has steadily increased over the past 20 years, and the four-year degree completion rate has become a central goal for UC campuses. Yet differences in graduation rates across race and ethnicity (Table 2) nonetheless suggest the need for targeted investments in the academic support infrastructures and attention to the makeup of UC faculty, staff, and senior leadership. In October 2018, UC staff was majority non-White (58.3 percent), but the majority of faculty was White, at 62.8 percent (University of California, n.d.).

To address limited faculty and staff diversity and in an effort to create climates that validate Latinx and underrepresented students of color, UC has taken a number of steps across the nine-campus system. For example, UC is supporting the development of an advisory council to strategically plan and invest in Latinx leadership within the system, including a Chicanx/Latinx Leadership Summit for faculty and staff leadership. These efforts are designed to support existing Latinx leaders and cultivate the next generation of Latinx leadership poised to contribute to the academic enterprise and support the growing Latinx student population. Because Latinx and many first-generation students that transition to UC are new to higher education, an infrastructure that scaffolds these students early with academic supports and mentorship, while also utilizing an asset-based approach, is critical to creating a climate for academic success.

To address limited faculty and staff diversity and in an effort to create climates that validate Latinx and underrepresented students of color, UC has taken a number of steps across the nine-campus system. For example, UC is supporting the development of an advisory council to strategically plan and invest in Latinx leadership within the system, including a Chicanx/Latinx Leadership Summit for faculty and staff leadership. These efforts are designed to support existing Latinx leaders and cultivate the next generation of Latinx leadership poised to contribute to the academic enterprise and support the growing Latinx student population. Because Latinx and many first-generation students that transition to UC are new to higher education, an infrastructure that scaffolds these students early with academic supports and mentorship, while also utilizing an asset-based approach, is critical to creating a climate for academic success.

Supporting Latinx Students: Recommendations for Practice

Since one-third of all HSIs are in California, it can serve as a bellwether state for effective public policy and systemic investments in HSIs (Excelencia in Education 2019b). The following recommendations represent possible mechanisms for engaging in authentic cultural shifts across the HSI systems that exist in California—and beyond the state—to equitably educate and support Latinx students.

Critically reflect on institutional infrastructures and modify campus units to become “Latinx responsive” to address the needs of diverse students. Given the rapid growth of Latinx and students of color in California and across higher education systems, institutions need to critically reflect on the cultural relevancy of their policies and practices, including student services, faculty composition, and campus and departmental climates that engage, challenge, welcome, and support Latinx and other underrepresented students. Strategies include expanding course availability, increasing faculty diversity, addressing the rising cost of college and meeting students’ basic needs, and improving meaningful work-study options for students to work on campus while also gaining valuable life skills.

Consider the multidimensional conceptual framework of “servingness.” HSIs, including emerging HSIs, should work to identify institutional systems, processes, and policies that may hinder the success of their Latinx students, especially in curricular and co-curricular spaces. Measuring Latinx-specific academic and nonacademic outcomes and student experiences is critical. Gina Garcia’s (2019) essay (a companion to this one) on servingness offers HSI leaders a broader perspective and application of this concept.

When Latinx students go to college, their whole family goes with them—higher education attainment fulfills the hopes and dreams of the generation before.

Implement culturally relevant approaches that engage Latinx students and their families. When Latinx students go to college, their whole family goes with them—higher education attainment fulfills the hopes and dreams of the generation before. Latinx students’ presence in a system of education that has long been considered only for elite sectors of society represents a tangible pathway to economic and social mobility for this pool of largely first-generation students. Engaging families in this process acknowledges the strong ties that many Latinx students have to their families and their bilingual, bicultural, and often binational or transnational backgrounds.

Foster greater connection to Latinx communities and partnerships with regional organizations. Institutions have the potential to serve their students and communities by developing and sustaining authentic partnerships with local nonprofits and community organizations that serve Latinx youth. For example, some community colleges are part of larger initiatives with local high schools and four-year institutions, while others open their doors to the community to use the library and host after-school programs or community meetings and events. These integrated models allow communities to engage with higher education in ways that are more authentic, and strengthens connections with Latinx families and the community organizations that serve them.

In Closing

The Public Policy Institute of California estimates that by 2030, the state of California will have a high demand for college-educated workers. In fact, the demand for an educated citizenry will exceed the supply (Johnson, Bohn, and Cuellar 2017). The public HSI systems in California have the potential to transform Latinx student experiences and outcomes—and thus, the state—by focusing greater attention on Latinx academic success, college completion, and pathways to graduate school and careers through targeted investments in practices that focus on increasing equity in postsecondary education. An asset-based approach to Latinx students, one that reinforces equitable access to institutions and services within these institutions, will undoubtedly produce incalculable returns for California and the nation.

References

ACT. 2017. ACT Profile Report–State: Graduating Class 2017, California. Iowa City: ACT. https://www.act.org/content/dam/act/unsecured/documents/cccr2017/P_05_059999_S_S_N00_ACT-GCPR_California.pdf.

Burdman, Pamela, Kathy Booth, Peter Riley Bahr, Jon McNaughtan, Grant Jackson, and Chris Thorn. 2018. Multiple Paths Forward: Diversifying Mathematics as a Strategy for College Success. San Francisco: WestEd and Just Equations.

California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office. 2019. “Alphabetic Listing of Community Colleges.” https://www.cccco.edu/Students/Find-a-College/College-Alphabetical-Listing.

CSU (California State University). 2018. Graduation Initiative 2025: Progress Report 2018. https://www2.calstate.edu/csu-system/news/Documents/GI2025-Fact-Sheet.pdf.

CSU (California State University). 2019. Graduation Initiative 2025. https://www2.calstate.edu/csu-system/about-the-csu/budget/2019-20-operating-budget/use-of-funds/Pages/graduation-initiative.aspx.

Contreras, Frances. 2011. Achieving Equity for Latino Students: Expanding the Pathway to Higher Education through Public Policy. New York: Teachers College Press.

Contreras, Frances. 2017. “Latino Faculty in Hispanic-Serving Institutions: Where Is the Diversity?” Association of Mexican American Educators (AMAE) Journal 11 (3): 223–250.

Contreras, Frances. 2018. “Cultivating the Next Generation of Latinx Leadership at the University of California.” Report prepared for the UC Chicanx/Latinx Leadership Summit, University of California Office of the President.

Contreras, Frances, Estela Mara Bensimon, and Lindsey E. Malcom. 2008. “An Equity-Based Accountability Framework for Hispanic Serving Institutions.” In Interdisciplinary Approaches to Understanding Minority Serving Institutions, edited by Marybeth Gasman, Benjamin Baez, and Caroline Sotello Viernes Turner, 71–90. New York: SUNY Press.

Contreras, Frances, and Gilbert J. Contreras. 2015. “Raising the Bar for Hispanic Serving Institutions: An analysis of College Completion and Success Rates.” Journal of Hispanics in Higher Education 14, no. 2 (April): 151–170.

Espinosa, Lorelle L., Jonathan M. Turk, Morgan Taylor, and Hollie M. Chessman. 2019. Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education: A Status Report. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Excelencia in Education. 2019a. Emerging Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs): 2017–18. Washington, DC: Excelencia in Education.

Excelencia in Education. 2019b. Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs): 2017–18. Washington, DC: Excelencia in Education.

Frankenberg, Erica, Jongyeon Ee, Jennifer B. Ayscue, and Gary Orfield. 2019. Harming Our Common Future: America’s Segregated Schools 65 Years After Brown. Los Angeles: The Civil Rights Project.

Gándara, Patricia, and Frances Contreras. 2009. The Latino Education Crisis: The Consequences of Failed Social Policies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ganga, Elizabeth, and Amy Mazzariello. 2018. Math Pathways: Expanding Options for Success in College Math. Denver: Education Commission of the States.

Garcia, Gina A. 2016. “Complicating a Latina/o-Serving Identity at a Hispanic Serving Institution.” The Review of Higher Education 40, no. 1 (Fall): 117–143. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2016.0040.

Garcia, Gina A. 2017. “Defined by Outcomes or Culture? Constructing an Organizational Identity for Hispanic-Serving Institutions.” American Educational Research Journal 54, no. 1S (April): 111S-134S. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216669779.

Garcia, Gina A. 2019. Defining “Servingness” at Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs): Practical Implications for HSI Leaders. Washington, DC: American Council on Education

Garcia, Gina A., Anne-Marie Núñez, and Vanessa A. Sansone. 2019. “Toward a Multidimensional Conceptual Framework for Understanding ‘Servingness’ in Hispanic-Serving Institutions: A Synthesis of the Research.” Review of Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0034654319864591.

Hurtado, Sylvia, René A. González, and Emily Calderón Galdeano. 2015. “Organizational Learning for Student Success: Cross-Institutional Mentoring, Transformative Practice, and Collaboration Among Hispanic-Serving Institutions.” In Hispanic-Serving Institutions: Advancing Research and Transformative Practice, edited by Anne-Marie Núñez, Sylvia Hurtado, and Emily Calderón Galdeano, 177–195. New York: Routledge.

Jackson, Jacob, and Kevin Cook. 2016. Improving College Graduation Rates: A Closer Look at California State University. San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California.

Johnson, Hans, Sarah Bohn, and Marisol Cuellar Mejia. 2017. Higher Education in California: Addressing California’s Skills Gap. San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 1995. “But That’s Just Good Teaching! The Case for Culturally Relevant Pedagogy.” Theory Into Practice 34, no. 3 (Summer): 159–165.

Malcom, Lindsey E., Estela Mara Bensimon, and Brianne Dávila. 2010. (RE)Constructing Hispanic-Serving Institutions: Moving Beyond Numbers Toward Student Success. Education Policy and Practice Perspectives. Ames, IA: Iowa State University.

Mejia, Marisol Cuellar, Olga Rodriguez, and Hans Johnson. 2016. Preparing Students for Success in California’s Community Colleges. San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California.

University of California. n.d. “Workforce Diversity.” https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/infocenter/uc-workforce-diversity.

Wagner, Chandi. 2017. School Segregation Then & Now: How to Move Toward a More Perfect Union. Alexandria, VA: Center for Public Education.

[1] The term “Latinx” refers to individuals of Latino/a, Chicana/o, Hispanic, Mexican, or Latin American descent. The “x” in the term negates the gender binary and presents a gender neutral option for the Latino racial/ethnic identity.

[2] Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs) are institutions with 25 percent or more total undergraduate Hispanic full-time equivalent student enrollment. HSIs received federal recognition in the 1992 reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, which also requires that institutions have high enrollment of needy students in addition to low educational and general expenditures. While most institutions receive HSI recognition when they reach this enrollment threshold, some HSIs were founded specifically to address the needs of Latinx students.