By Cecilia Rios-Aguilar and Regina Deil-Amen

Who Are the Students Community Colleges Serve?

The typical college student is no longer the image many of us hold in our heads—an 18- to 22-year-old who leaves his or her parents’ home for the first time, ready to begin the journey at an ivy-walled four-year college or university. Rather, many of today’s college students are beyond the age of 24, employed at least part time, and raising a family. Approximately half are low-income and financially independent from their parents, and a third are students of color (Deil-Amen 2015; Ma and Baum 2016).

Most notably, the majority of today’s students are beginning or continuing their postsecondary education in our nation’s community colleges (Deil-Amen 2015), which offer a critical point of access to first-time college-goers and students moving up the socioeconomic ladder and out of poverty (Goldrick-Rab, Richardson, and Hernandez 2017).

However, it is also vital to acknowledge that many of these students have not been served adequately by the educational sys- tem prior to their enrollment in community college (Deil-Amen and DeLuca 2010). Examining recent national data, scholars found that community colleges, in addition to enrolling many adults who return to school, now serve the underserved half of high school students (Bittinger et al. 2018). Deil-Amen and DeLuca (2010) define the underserved half as “an underclass of students who are neither college ready nor in an identifiable career curriculum” (28).

Traditionally, secondary and postsecondary students are thought of as being placed on either an academic or vocational track. However, Deil-Amen and DeLuca (2010) suggest that students are actually divided across three categories: academic, vocational, and underserved. Students in the academic category are exposed to a rigorous college preparatory curriculum and are well-prepared for success in college and rewarding occupations. Vocational students are prepared for the labor force through their involvement in either high school or postsecondary career and technical education programs. The underserved students, by contrast, are not prepared academically for college and are also not enrolled in any career curriculum or program.

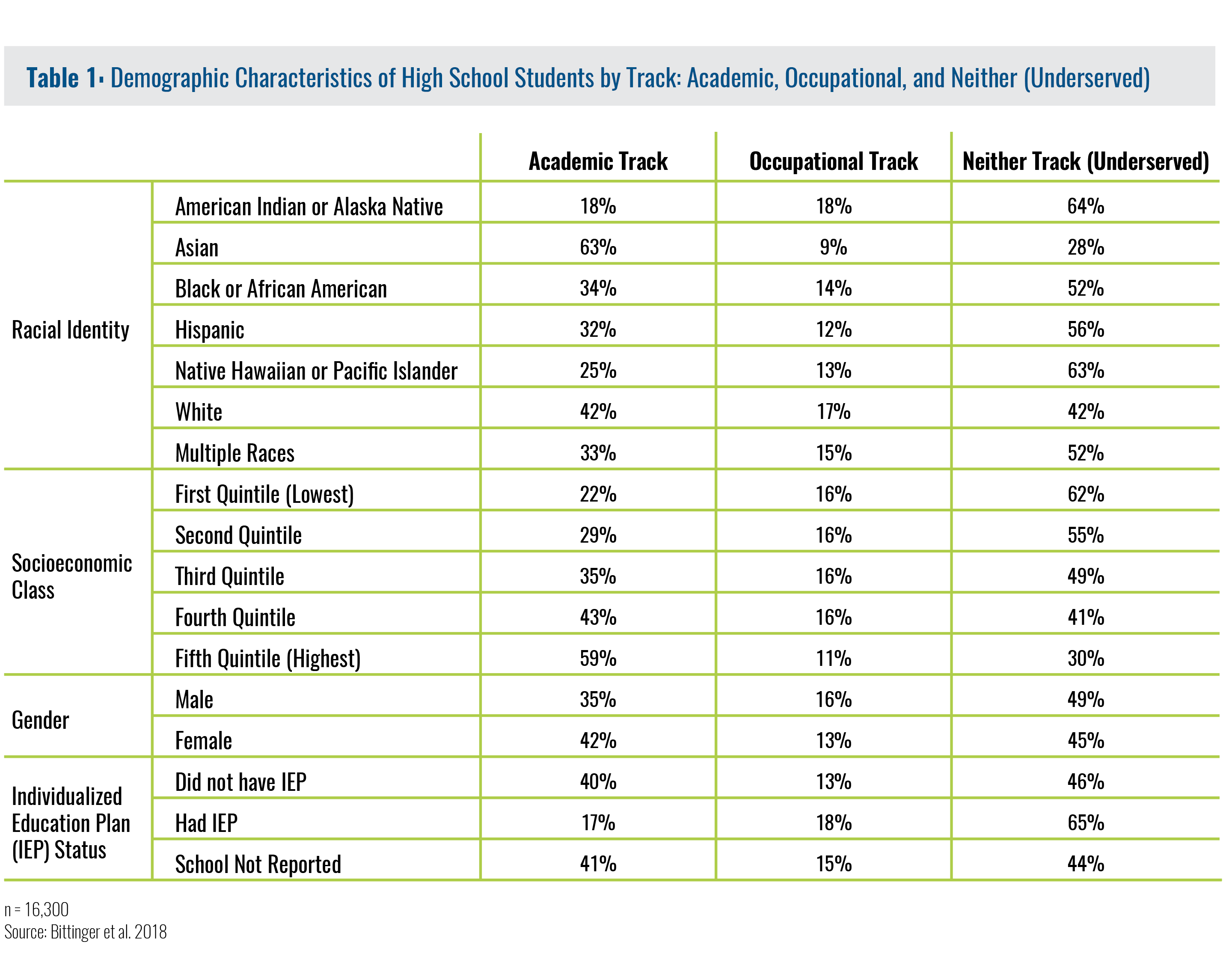

As Table 1 reveals, this underserved group is composed of mostly low-income students and students of color. Furthermore, students in the underserved group are overrepresented in community colleges and, more specifically, in certificate programs and remedial or developmental classes (Bittinger et al. 2018).

Because of low tuition, convenient locations, and open admissions, community colleges enroll a high proportion of under- graduates who are marginalized by the educational system. But despite high enrollment, community colleges have notoriously low completion rates. As the data show, many students who enter the community college system are likely to get trapped in remedial classes and eventually drop out without transferring or completing any degree or certificate. If not served properly, these students become the new forgotten half—the half of college students who accumulate credits, but end up with no degree or credential, and few marketable skills (Rosenbaum et al. 2015).

The Community College Disadvantage

Community colleges have been a staple of access for a substantial proportion of the U.S. population for more than half a century. Since World War II, most attempts to universalize higher education have resulted in dramatic expansion not at the top of the higher education hierarchy, but at the bottom—namely, at the least selective public two- and four-year institutions. While positive in terms of increased access, this movement solidifies existing inequalities by increasing access at resource- constrained, open-access institutions, rather than at the more selective institutions with more resources (Roksa et al. 2007). That increase in the volume of students, combined with disparities in public funding, puts community colleges at a disadvantage when it comes to student success.

Most public postsecondary institutions, including community colleges, are financed through a combination of state appropriations and tuition revenues, and for community colleges in particular local funding is vital (Baime and Baum 2016). In roughly half of all states, community colleges receive some amount of appropriations from their local government, too. Reflecting the broader state government disinvestment in higher education (Ma et al. 2015), virtually all community colleges have now become increasingly reliant on tuition as a revenue source. In fact, the proportion of expenditures covered by net tuition revenue has increased from 26 percent to 39 percent over a decade from 2002–03 to 2012–13 (Baime and Baum 2016). Furthermore, spending per full-time equivalent student over a 10-year period from 2001 to 2011 increased at public and private research universities by $2,700 and $11,000, respectively, while community colleges saw a decline in spending of $904 during the same period of time (Kahlenberg 2015). These inequities are especially problematic due to the fact that community college students are more vulnerable and need more resources and support structures.

College and university tuition and related costs have risen sharply, especially at selective, four-year institutions, further restricting access. Tuition and fees at community colleges continued to remain lower and more affordable. The College Board reported that the average in-state tuition and fees at public two-year institutions was $3,570, compared with $9,970 at public four-year and $34,740 at private nonprofit four-year colleges (Ma et al. 2017).

While tuition and fees are a substantial cost, they are not the only costs associated with attending college today. In addition to paying tuition, students and their families must often cover costs associated with transportation, housing, food, health care, and child care, as well as lost or reduced wages, to name only a few. So, while tuition may seem relatively affordable at community colleges, the total costs of enrolling in higher education, including community college, are still high for the vast majority of students.

Federal financial aid has not kept pace with rising college costs, concentrating low-income students—many of whom are students of color—at community colleges. The importance of financial aid is compounded for this demographic, given that the majority of community college students have greater financial needs than traditional students attending four-year research institutions.

In short, such disparities in public funding and financial aid, in addition to a large and consistent influx of underserved students, exacerbate the challenges community colleges face in addressing the structural barriers preventing student success (Baime and Baum 2016). Community colleges already serve the underserved half of high school students; these students are now at risk of becoming the new forgotten half of community college students: credits but no degree.

Given these trends, we must examine what success means at community colleges. Societally, we’ve experienced a turn away from the idea of higher education serving the public good and toward higher education as a private good to be consumed. As a result, public support of higher education through tax-based funding has declined, particularly in places where the college demographic is more heavily composed of students of color, with voters more heavily white and older (Brunner and Johnson 2016). We’ve seen an erosion of the belief in higher education serving the public good just as more students of color have gained access.

Community colleges already serve the underserved half of high school students; these students are now at risk of becoming the new forgotten half of community college students: credits but no degree.

As the desire for public support has declined, the “accountability” movement has exploded, calling upon institutions—and their students—to prove they deserve public funding. This movement has been particularly problematic for community colleges, especially “performance-based funding,” which adjusts the funding allocated based on various success measures, including completion (D’Amico et al. 2014; McKinney and Serra Hagedorn 2017). However, at community colleges, due to their open-access nature and underserved students, less can be assumed about the level of commitment students have to their degree or transfer goals. The less concrete and more-likely shifting nature of those goals is not accounted for when student success outcomes are measured (Bailey, Jenkins, and Leinbach 2007).

As a result, we must be open and flexible when defining success in the community college sector. The fluid development of aspirations and exploration of future goals is a fundamental feature of such low-cost, open-access institutions, and is highly incompatible with rigid performance measures. Policymakers and administrators must understand the incentive structures accountability creates, because it may exacerbate inequities if funding formulas are not grounded in an understanding of students’ lives and institutional realities.

To this end, there are recent examples (see Melguizo and Witham 2018) that examine the potential of various funding formulas to achieve three interrelated and crucial goals: equity, efficiency, and student success. In 2018, Governor Jerry Brown of California proposed a budget that applied a new outcomes-based funding supplement (or what he calls the student success incentive), which will start impacting California community colleges in the 2018–19 year. The formula seems to provide flexibility to institutions and important incentives to increase productivity (broadly measured), with particular attention to closing equity gaps.

The Completion Challenge: How to Better Support Community Colleges

Because community colleges serve so many marginalized students, especially low-income and students of color, any national response to growing inequality must include these institutions. But some community colleges are serving students better than others.

A recent report by Baime and Baum (2016) found that differences across community colleges are wide and present serious challenges for national policies that promote student access and success. For instance, tuition is an important obstacle for many students in some states, but not in others. Some scholars have argued that the varying missions and goals of community colleges have created institutional structures akin to “mazes” and a “shapeless river” (Scott-Clayton 2015) that leave students confused and unable to make timely and informed decisions, thus reducing their chances of success. To make a tangible impact on student success, policymakers and community college administrators, faculty, and staff should continually reexamine their practices and ways of thinking to overcome the structural, pedagogical, and institutional barriers that frequently create the forgotten half—leaving students of color with no college degree and few tools to reap labor market rewards.

One possible solution to address these structural barriers is redesigning community colleges to create clear, coherent, and concise “guided pathways” (Bailey, Jaggars, and Jenkins 2015) to help students navigate their educational journeys with greater success. Instead of offering an overwhelming array of courses, schedules, and programs, institutions could rethink the way they offer their services. For example, some colleges are working backward from the end goal of a degree with instant value in the labor market, or the ability to transfer to four-year institutions. These colleges create more structured pathways with maps— available in their course catalogs and websites—that clearly state the classes students need to take each term. Other colleges are hiring academic coaches and additional career counselors to help students stick to their pathways and complete their goals.

The building of such pathways requires great human and material resources to meet the academic and social needs of diverse students and their range of life circumstances. This includes additional approaches beyond the pathways themselves, for example: flexible class schedules; high-quality online courses; competency-based educational options; access to emergency funds; off-hour counseling and advising; child care; and food pantries. However, no matter how simple and few options are presented to students, “there will still be a number of students who enroll in one course at a time, who stop out, who take years to find their academic or occupational path, whose past blunders and transgressions continue to exact a material and psycho- logical price, whose personal history of neglect and even trauma can cripple their performance” (Rose 2016). Therefore, while simplification may bring benefits to some students, simplification by itself will not be sufficient to redress inequities. Marginalized community college students, particularly racial and ethnic minorities, also need faculty, staff, and administrators who care for them and understand who they are and where they come from, in order to succeed academically and in life.

Students’ Academic and Occupational Trajectorie

While community colleges pride themselves on opening their doors to students from all walks of life and being the entry point to higher education, access is not enough. Without resources, services, networks, and a clear path to success, access is only an empty promise. Research has continuously affirmed the fact that too many low-income and racial and ethnic minority students enter community colleges with feelings of being different and ill-prepared for the college learning experience.

While recommendations often focus on structurally redesigning the way community colleges operate and serve students, the main point of contact and connection for community college students occurs within the classroom (Chang 2005; Deil- Amen 2011). Indeed, Deil-Amen (2011) finds two-year college students’ decisions to persist are shaped by socio-academic integrative moments—interactions within and just outside the classroom with instructors and peers who enhance belonging and encourage or reinforce students’ academic identity. Moreover, the research of Rebecca Cox (2009) demonstrates how the psychological and emotional aspects of classroom experiences cannot be extracted from the cognitive elements of learning.

To address these issues, faculty in community colleges could consider more systematic efforts to infuse asset-based, culturally responsive instructional materials and use pedagogical practices aligned with these materials to address equity gaps and help students succeed. Most cultural-specific efforts have occurred in K–12 contexts but can be applied at community college classes, many of which cover content similar to secondary classrooms. Additionally, a few examples do exist of how college faculty can use non-deficit approaches such as funds of knowledge and community cultural wealth (Mora and Rios-Aguilar 2018; Solórzano, Huerta, and Giraldo 2018; Neri 2017) to rethink career and technical education and to help other marginalized students succeed academically (Kiyama and Rios-Aguilar 2017).

With respect to creating more welcoming environments, it is important to start with focusing on providing students with services that meet their primary needs. In K–12 schooling, the idea that hunger impedes learning is widely accepted and serves as a rationale for the provision of reduced-priced meals. This is not the case in higher education. Broton and Goldrick-Rab (2017) documented that more than half of community college students experience food insecurity and about one-third reported at least one challenge related to housing affordability and stability. Their findings suggest that if we want students to be able to focus on learning and completing their academic goals, we must pay attention to serving their material needs.

Community colleges, and those who work and teach in these institutions, should certainly be lauded for their dedication to providing access and opportunity for so many of our nation’s students. Community colleges have been positioned to deliver the promise of higher education to the most underserved populations of students, but with inadequate funding structures that continue a pattern of persistent inequity for students of color.

Rather than thinking of individual students at risk, higher education must think more systematically about how institutions can create equal opportunities throughout the higher education hierarchy. Simplifying the pathway and enhancing cultural responsiveness can improve practice, but adequately meeting the material and financial needs of community college students needs to be at the forefront of efforts to address ongoing inequities in opportunity.

The underserved forgotten half is a growing problem in higher education that disproportionately presents challenges for students of color. It is not enough simply to get students into the classroom; they must be enabled to succeed in order to realize the promise of higher education.

References

Bailey, Thomas, Shanna Smith Jaggars, and Davis Jenkins. 2015. Redesigning America’s Community Colleges. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bailey, Thomas, Davis Jenkins, and D. Timothy Leinbach. 2007. The Effect of Student Goals on Community College Performance Measures. CCRC Brief Number 33. New York: Community College Research Center, Columbia University.

Baime, David, and Sandy Baum. 2016. Community Colleges: Multiple Missions, Diverse Student Bodies, and a Range of Policy Solutions. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED570475.pdf.

Bittinger, Joshua, Cecilia Rios-Aguilar, Ryan Wells, and David Bills. 2018. “Credentials with (Economic) Value? Unmasking Inequities in the Sub-baccalaureate Sector.” Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, New York, NY.

Broton, Katherine M., and Sara Goldrick-Rab. 2017. “Going Without: An Exploration of Food and Housing Insecurity Among Undergraduates.” Educational Researcher 47 (2): 121–133.

Brunner, Eric J., and Erik B. Johnson. 2016. “Intergenerational Conflict and the Political Economy of Higher Education Funding.” Journal of Urban Economics 91: 73–87.

Chang, June C. 2005. “Faculty Student Interaction at the Community College: A Focus on Students of Color.” Research in Higher Education 46 (7): 769–802.

Cox, Rebecca D. 2009. “‘It Was Just That I Was Afraid’ Promoting Success by Addressing Students’ Fear of Failure.” Community College Review 37 (1): 52–80.

D’Amico, Mark M., Janice N. Friedel, Stephen G. Katsinas, and Zoë M. Thornton. 2014. “Current Developments in Community College Performance Funding.” Community College Journal of Research and Practice 38 (2–3): 231–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2014.851971.

Deil-Amen, Regina. 2015. “The ‘Traditional’ College Student: A Smaller and Smaller Minority and Its Implications for Diversity and Access Institutions.” In Remaking College: The Changing Ecology of Higher Education, edited by Michael W. Kirst and Mitchell L. Stevens, 134–168. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Deil-Amen, Regina. 2011. “Socio-Academic Integrative Moments: Rethinking Academic and Social Integration Among Two-Year College Students in Career-Related Programs.” The Journal of Higher Education 82 (1): 54–91.

Deil-Amen, Regina, and Stefanie DeLuca. 2010. “The Underserved Third: How Our Educational Structures Populate an Educational Underclass.” Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk 15 (1–2): 27–50.

Goldrick-Rab, Sara, Jen Richardson, and Anthony Hernandez. 2017. Hungry and Homeless in College: Results from a National Study of Basic Needs Insecurity in Higher Education. Madison, WI: Wisconsin HOPE Lab.

Kahlenberg, Richard D. 2015. How Higher Education Funding Shortchanges Community Colleges. The Century Foundation. http://tcf.org/blog/detail/how-higher-education-funding-shortchanges-community-colleges.

Kiyama, Judy Marquez, and Cecilia Rios-Aguilar, eds. 2017. Funds of Knowledge in Higher Education: Honoring Students’ Cultural Experiences and Resources as Strengths. New York: Routledge.

Ma, Jennifer, and Sandy Baum. 2016. Trends in Community Colleges: Enrollment, Prices, Student Debt, and Completion. College Board.

Ma, Jennifer, Sandy Baum, Matea Pender, and D’Wayne Bell. 2017. Trends in College Pricing 2017. Trends in Higher Education Series. College Board. https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2017-trends-in-college-pricing_0.pdf.

Ma, Jennifer, Sandy Baum, Matea Pender, and D’Wayne Bell. 2015. Trends in College Pricing 2015. Trends in Higher Education Series. College Board. https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2015-trends-college-pricing-final-508.pdf.

McKinney, Lyle, and Linda Serra Hagedorn. 2017. “Performance-Based Funding for Community Colleges: Are Colleges Disadvantaged by Serving the Most Disadvantaged Students?” The Journal of Higher Education 88 (2): 159–182.

Melguizo, Tatiana, and Keith Witham. 2018. Funding Community Colleges for Equity, Efficiency, and Student Success: An Examination of Evidence in California. New York: The Century Foundation. https://tcf.org/content/report/funding-community-colleges-equity-efficiency-student-success-examination-evidence-california.

Mora, Juana, and Cecilia Rios-Aguilar. 2018. “Aligning Practice with Pedagogy: Funds of Knowledge for Community College Teaching.” In Funds of Knowledge in Higher Education: Honoring Students’ Cultural Experiences and Resources as Strengths, edited by Judy Marquez Kiyama and Cecilia Rios-Aguilar, 145–159. New York: Routledge.

Neri, Rebecca Colina. 2017. “Learning from Students’ Career Ideologies and Aspirations: Utilizing a Funds of Knowledge Approach to Reimagine Career and Technical Education (CTE).” In Funds of Knowledge in Higher Education: Honoring Students’ Cultural Experiences and Resources as Strengths, edited by Judy Marquez Kiyama and Cecilia Rios-Aguilar, 160–174. New York: Routledge.

Roksa, Josipa, Eric Grodsky, Richard Arum, and Adam Gamoran. 2007. “United States: Changes in Higher Education and Social Stratification.” In Stratification in Higher Education: A Comparative Study, edited by Yossi Shavit, Richard Arum, and Adam Gamoran, 165–191. Rose, Mike. 2016. “Reassessing a Redesign of Community Colleges.” Inside Higher Ed, June 23, 2016.

Rosenbaum, James, Caitlin Ahearn, Kelly Becker, and Janet Rosenbaum. 2015. The New Forgotten Half and Research Directions to Support Them. New York: William T. Grant Foundation.

Scott-Clayton, Judith. 2015. “The Shapeless River: Does a Lack of Structure Inhibit Students’ Progress at Community Colleges?” In Decision Making for Student Success: Behavioral Insights to Improve College Access and Persistence, edited by Benjamin J. Castleman, Saul Schwartz, and Sandy Baum, 102–123.

Solórzano, Daniel G., Adrian H. Huerta, and Luis G. Giraldo. 2018. “From Incarceration to Community College: Funds of Knowledge, Community Cultural Wealth, and Critical Race Theory.” In Funds of Knowledge in Higher Education: Honoring Students’ Cultural Experiences